My name is Chris Lischewski and I was the President and CEO of Bumble Bee Seafoods for almost 20 years. On June 16, 2020 I was sentenced to 40 months in prison for supposedly being the ringleader of an ‘overarching conspiracy to fix the prices of canned tuna in the U.S. from November of 2010 through December of 2013’. The problem? There was no price fixing.

My sentencing culminates a five year saga during which the Department of Justice prosecuted the tuna industry, perhaps the most competitive category in U.S. grocery stores, and drove Bumble Bee into bankruptcy. I was the only individual in the $2.7 billion U.S. shelf stable seafood category brought to trial in this purported conspiracy. I was found guilty of a crime I did not commit and a crime where there is no victim.

How can I make this statement when Bumble Bee, StarKist and several of their executives pled guilty to price fixing and Chicken of the Sea confessed to this crime in exchange for amnesty? Let’s evaluate the facts and then look at the overwhelming power the Government has to prosecute these kinds of cases and consistently achieve guilty pleas and verdicts.

Background To The Criminal Investigation

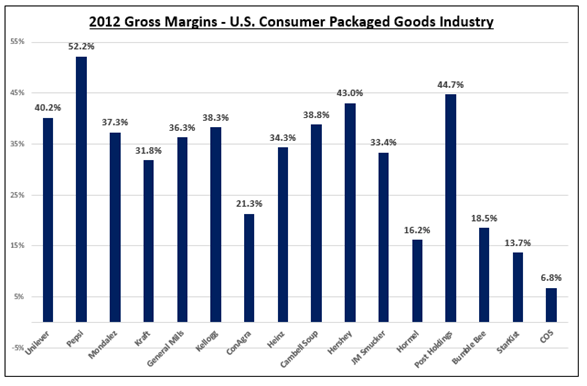

The canned tuna industry is perhaps the most competitive category in all of U.S. grocery. Gross margins are less than half of what most U.S. branded food companies earn (see the last three columns of the chart below), consumption has been declining for more than 20 years, and virtually every one of our retail customers has a business strategy to replace our brands with their own private labels.

These market conditions explain why Thai Union, the largest canned tuna company in the world and owner of Chicken of the Sea in the U.S., entered into a transaction to acquire Bumble Bee in late 2014. The merger of the two businesses was expected to achieve more than $40 million in cost synergies which would have improved the combined company’s cost structure and would have resulted in lower prices for U.S. consumers.

Upon completion of the transaction the canned tuna market share of the combined Bumble Bee / Chicken of the Sea entity would have been about 40% – 45%, which is similar in size to StarKist. Given the potential anti-trust concern from such a high level of concentration in the U.S. canned tuna category, both Thai Union / Chicken of the Sea and Bumble Bee expected a detailed review of the proposed combination by the U.S. Department of Justice. In anticipation of this review, both companies hired outside legal counsel to assist in evaluating the feasibility of the transaction and neither company was informed of any price fixing concerns. Both companies entered the transaction confident that the pro-competitive aspects of the combination would lead to approval by the Department of Justice.

Following Thai Union’s announcement of the proposed acquisition of Bumble Bee in December of 2014, the Government began its process to review the transaction and either approve it or challenge it on anti-trust grounds. At some point, this review uncovered concerns which led to the July, 2015 announcement by the Department of Justice of a criminal investigation into price fixing by the three major tuna companies in the U.S.: StarKist, Bumble Bee and Chicken of the Sea.

Within weeks of announcing the criminal investigation, it was made known that Chicken of the Sea was the whistle blower which enabled it to negotiate for full amnesty from prosecution for the company and its employees in return for its agreement to cooperate with the Government in the price fixing investigation. This was followed 18 months later by guilty pleas from two Bumble Bee executives and one StarKist executive, all three of whom were employed in sales and trade marketing (pricing) roles. The guilty pleas by their employees forced both Bumble Bee and StarKist to plead guilty in May of 2017 and October of 2018, respectively.

The Per Se Rule

The Department of Justice conducted its price fixing investigation, and ultimate prosecution of me, under a theory known as the “Per Se” rule. The Sherman Antitrust Act was interpreted to include the Per Se rule in 1898 when price fixing was considered a misdemeanor with a maximum fine of $1,000. That has since evolved and a Per Se violation is now a felony crime carrying a maximum prison term of 10 years and a $1 million fine.

Under the Per Se rule, the agreement to fix prices is the crime and there is no requirement to show proof of any price-fixing effect. Said another way, the Government was not required to prove any financial impact or financial harm from the purported tuna price fixing agreement. If the Government could convince the jury that there was an agreement to fix prices, even if it lasted a short time, was never implemented, and had no effect on prices, the jury would be required to return a guilty verdict.

The Per Se rule sets a very low bar for the Government to overcome to achieve a guilty verdict. If it were not for this rule, there would have been no finding of a conspiracy in the U.S. tuna industry as the evidence clearly showed that there was no financial impact of any purported price fixing. The evidence proved that no customers were over-charged for their canned tuna – but under the Per Se rule, the fact that there was no financial harm didn’t matter.

Evidence that Demonstrates an Intensely Competitive Market

The Government alleged that the tuna industry fixed prices from November of 2010 to December of 2013. During this period of time canned tuna prices on grocery store shelves went up significantly. However, this had nothing to do with price fixing; it was due to tuna costs which rose to unprecedented levels in 2011 and 2012.

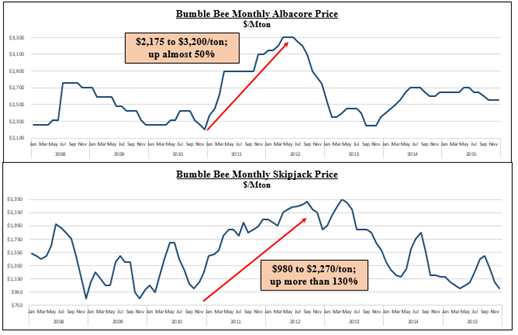

Unforeseen circumstances led to the tremendous cost inflation. Albacore, the species of tuna used in solid white, was impacted by the tsunami that hit the coast of Japan in March, 2011 resulting in the Fukushima nuclear disaster. The resulting loss of electricity throughout large areas of Japan destroyed much of the frozen tuna in Japan’s cold store facilities and long line fishing vessels that traditionally fished for albacore tuna switched to other species of tuna (bigeye and yellowfin) to rebuild Japanese inventories.

Skipjack, the species of tuna generally used to produce chunk light, faced different supply challenges in 2011 and 2012 including a strong La Nina weather event in the Pacific Ocean and increasing conservation measures that incorporated temporary fishery closures.

These events led to unanticipated tuna supply shortages resulting in record fish cost inflation. Albacore reached $3,200/ton, up almost 50% from the end of 2010, and skipjack reached $2,270/ton, up more than 130%. To put this in perspective, albacore tuna makes up about 80% of the cost of a can of solid white tuna and skipjack tuna represents about 65% of the cost of a can of chunk light tuna.

Bumble Bee attempted to pass through the higher fish costs in pricing to maintain our profit margins. However, given the intense competitive environment, we were not able to do so. This led to pressure on gross margins and our profitability suffered between 2011 and 2013. We did not regain our historical profit margins until 2014 when fish prices fell back to more normal levels and the competitive environment became more rational.

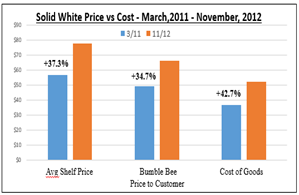

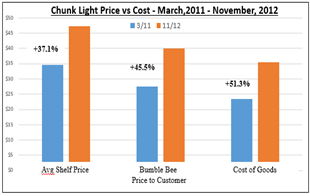

This is demonstrated in the following charts that show Bumble Bee’s change in the average price charged to customers compared to the change in the cost of our products between March, 2011 and November, 2012. The price of solid white albacore to customers increased by 34.7% while costs were up 42.7%. Similarly, the price of chunk light tuna went up 45.5% while cost was up 51.3%. The inability to pass through the higher costs had a significant effect on margins and profitability.

Had the tuna industry been engaged in a price fixing conspiracy, one would have expected to see pricing to customers exceed the increase in the cost of canned tuna. This did not happen.

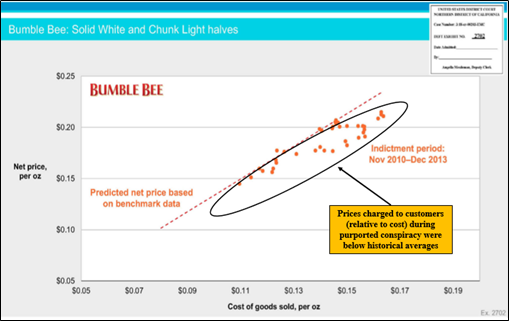

An analysis conducted by Dr. Joseph Levinsohn, an expert witness called by the defense and a long tenured economist at Yale University, further demonstrated that there was no effect of the purported price fixing conspiracy. Based on a 15 year analysis of actual monthly price and cost data from 2002 – 2016, Dr. Levinsohn demonstrated that prices charged during the purported conspiracy were lower than relative prices (actual price relative to actual product cost) predicted by historical data. The conclusion of this analysis is that customers were under-charged during the purported conspiracy period. This is the exact opposite of price fixing and is what you would expect to see in a market with robust competition.

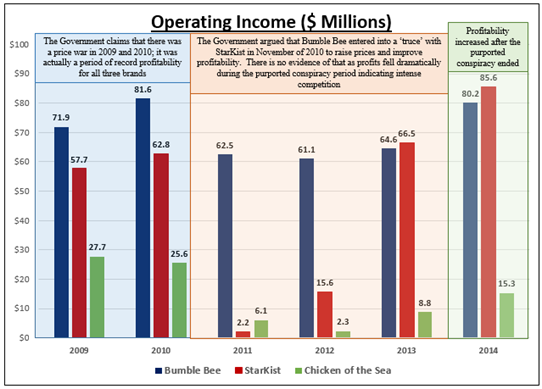

The theory of the price fixing offense that the Government presented to the jury ran as follows. It claimed that during 2009 and 2010, the U.S. tuna industry was experiencing intense competition which they referred to as a price war. They asserted that in an effort to meet the profitability commitments I had made to Lion Capital, the private equity group which acquired Bumble Bee in December of 2010, I instructed my executives to negotiate a ‘truce’ with StarKist in November, 2010 whereby both companies would agree to price less aggressively. The Government argued that this “truce” agreement in late 2010 led to inflated prices and was the beginning of the price fixing conspiracy.

The facts don’t support this theory. While 2009 and 2010 were years of robust competition, there wasn’t a price war. These were two of the most successful years that our industry has experienced and all three tuna companies achieved record profitability. Conversely, profitability plummeted in 2011 – the year the Government claimed was the start of the conspiracy — as both StarKist and Chicken of the Sea attacked Bumble Bee relentlessly with ultra-aggressive pricing leading to extremely poor financial performance. 2011 was not the beginning of a price fixing conspiracy in the U.S. tuna category, it was the beginning of rapidly escalating fish costs and intense, even irrational, competitive activity.

During a price fixing conspiracy you would expect to see increasing profits but in 2011, the first full year of the purported conspiracy, Bumble Bee Operating Income dropped 23%, StarKist was down a whopping 96.5%, and Chicken of the Sea was down by more than 75%.

Profits remained depressed in 2012 with Chicken of the Sea performing even worse than it did in 2011. A gradual recovery began in 2013 but this had less to do with pricing and more to do with fish costs returning to normal levels. Interestingly, in 2014 after the purported conspiracy had ended, all three companies improved their profitability despite the absence of any ‘price fixing’.

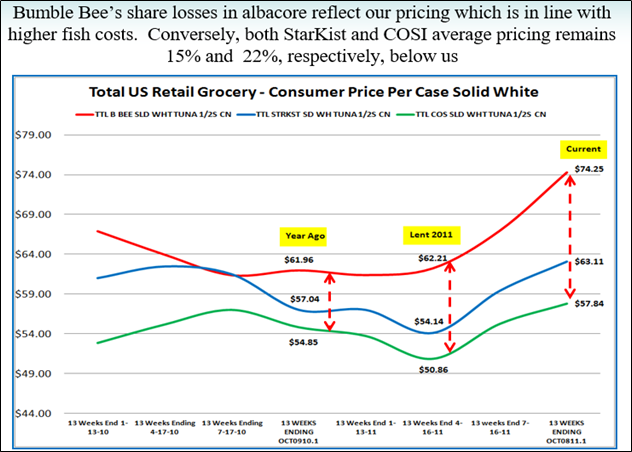

Throughout my trial, my defense team provided extensive evidence and factual data demonstrating the intense competitive environment that existed between 2011 and 2013. One example is the following chart from a Bumble Bee Board presentation that shows Bumble Bee (red line) raising its prices for solid white albacore consistent with higher fish costs in 2011 while both StarKist (blue line) and Chicken of the Sea (green line) held back their pricing so they could attack Bumble Bee and take market share. StarKist pricing moved from relative parity with Bumble Bee in late 2010 to a discount of 15% by the end of 2011. Chicken of the Sea, always the discounter in the tuna category, doubled its price discount from about 12% to 22%. This did not reflect a period of price fixing, it reflected a period of intense competition.

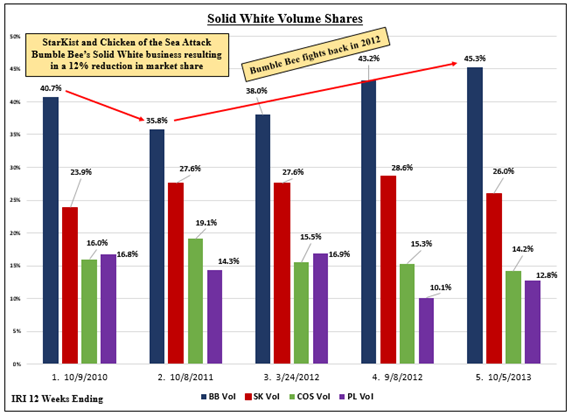

This competitive aggression was evident in market share data. Looking at solid white albacore – where Bumble Bee makes the bulk of its profit — it is evident that the aggressive pricing implemented by both StarKist and Chicken of the Sea negatively impacted Bumble Bee throughout 2011 as our solid white market share dropped by 12%. This continued into early 2012 when Bumble Bee made the decision to fight back and regain our share. Again, this was not evidence of a price fixing conspiracy, it was evidence of an extremely competitive market.

Customer level pricing data also demonstrated significant competition. My defense team presented statistics showing the actual monthly prices that the brands charged customers for canned tuna over the purported conspiracy period. We also showed weekly market share trends. As would be expected in a market with vibrant competition, there were significant differences by customer and by brand. The evidence showed no pattern in customer level pricing which is something that would have been visible if the companies were engaged in price fixing.

To recap, the financial data that my defense team presented proved that there was no effect of the purported collusion on any retail customer during the period of November, 2010 through December, 2013. The Government never made an attempt to introduce their own economist and didn’t present any other evidence to challenge our assertions or to support its allegation of price fixing. That’s because under the Per Se rule, it did not need to provide evidence of any price fixing ‘effect’.

The Governments Prosecution

The Government’s prosecution of me was based largely on the testimony of four cooperating witnesses, Scott Cameron and Ken Worsham, formerly the SVP’s of Sales and Trade Marketing, respectively, at Bumble Bee, Steve Hodge, the former SVP of Sales and Trade Marketing at StarKist, and Shue Wing Chan, the former President and CEO of Chicken of the Sea. The term “cooperator” is used to describe someone who has pled guilty (or, in Chan’s case, received amnesty) and has then agreed to cooperate with the Government in return for a reduced sentence or some other benefit. As part of their cooperation deal they promise to tell the truth. However, the Government ultimately determines how effective the cooperation has been and how it will affect the sentencing recommendation it will make on the cooperators behalf. This gives the cooperators a strong incentive to testify in a manner that pleases the Government – in this case, to obtain a guilty verdict against me.

The Cooperators

Scott Cameron – SVP Sales, Bumble Bee: After reviewing all of the evidence, I am confounded by Cameron’s guilty plea. Cameron met with the Government on 21 occasions leading up to my trial during which time his testimony changed substantially. Cameron consistently stated that he colluded with Chuck Handford, StarKist’s VP of Trade Marketing from the beginning of the purported conspiracy in November of 2010 until Handford left StarKist in September of 2011. However, while Cameron initially stated that he did not inform me of his communication with Handford, that eventually changed to him testifying that I was the one who told him to establish the relationship in late 2010 after which he regularly kept me informed of their discussions.

Handford had worked for Bumble Bee in the past and was friends with Cameron. While it appears they talked regularly, Handford has vehemently denied any involvement in an agreement to fix prices and he was never charged by the Government. Handford stated that he always competed aggressively and this was evident not only in StarKist’s market share gains in 2011, but also in its financial performance with Operating Income plummeting by more than 95% that year.

Bumble Bee is the only company that pled guilty to participation in price fixing during the period of November, 2010 to October, 2011 (StarKist pled guilty for the period of November, 2011 through December, 2013 and Chicken of the Sea admitted participation in price fixing from March, 2012 through June, 2013). I can only surmise that the Government’s threat of prosecution resulted in Cameron pleading guilty to a crime he did not commit as I’m not sure how we could have colluded with ourselves.

Ken Worsham – SVP Trade Marketing, Bumble Bee: Worsham testified that he colluded with Hodge of StarKist from November, 2011 through December, 2013. Hodge had added trade marketing (pricing) to his sales responsibilities in November of 2011 after the departure of Handford. During Worsham’s 32 meetings with the Government leading up to my trial, he said that he and Hodge coordinated two list price increases during 2012, a year of record cost inflation, and then coordinated ‘quarterly pricing guidance’ until Hodge was terminated by StarKist in December of 2013. Worsham said he kept me informed of his communication with Hodge in private one-on-one meetings but he could not provide details of even one such meeting.

While evidence showed that Worsham and Hodge were in regular communication, the idea that they could fix the prices of canned tuna is unrealistic and naïve. Our principal customers, Walmart, Kroger, Costco, Albertsons, etc., are large and extremely sophisticated buyers who have tremendous purchasing leverage. They negotiate individually with all three brands and they all have their own private labels that they source from third party co-packers giving them a direct insight into product cost. With canned tuna being a global commodity, our customers have the ability to verify our costs not only by comparing competitive quotes, but also by looking at cost changes in their own private label products and by analyzing the numerous tuna cost indices that are readily available on the internet.

Steve Hodge – SVP Sales and Trade Marketing, StarKist. Hodge testified for two days and my name was rarely mentioned. During the period of the alleged conspiracy he had no contact with me of any kind and he testified that my name never came up in any conversations he had with Worsham.

Shue Wing Chan – President & CEO, Chicken of the Sea. The real enigma was Shue Wing Chan, the former President and CEO of Chicken of the Sea (and cousin of Thai Union President and CEO, Thiraphong Chansiri). Chan testified that he had reached an ‘understanding’ with me to ‘not promote (discount) aggressively’ from March of 2012 through June of 2013. However, when questioned about the details, Chan admitted that the ‘understanding’ was only in his mind. Chan conceded that I never once acknowledged an agreement or understanding. Furthermore, Chan never told anyone at Chicken of the Sea about his ‘understanding’ and could not provide evidence of even one promotion he changed to adhere to our purported agreement.

If there really was an ‘understanding’ between Chan and me it would have been identified during the anti-trust legal reviews that had been carried out by Thai Union / Chicken of the Sea and Bumble Bee prior to the execution of the acquisition agreement in late 2014. My only explanation of Chan having admitted to this offense is that it enabled Chicken of the Sea to entice the Department of Justice to accept them as the ‘whistle blower’ whereby they (and their employees) were granted full amnesty from prosecution.

Chan’s contradictory testimony aside, the evidence at trial (including the financial data discussed earlier) showed that Chicken of the Sea never stopped promoting aggressively. While Chan said he reached an ‘understanding’ with me in an effort to improve his profitability, Chicken of the Sea’s Net Income showed a loss in both 2011 and 2012 while only performing slightly above breakeven in 2013.

Did Justice Prevail?

To sum up, my defense team proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that there was no financial data that corroborated the Government’s claim of a price fixing conspiracy in the canned tuna industry. But under the Per Se rule, the financial data didn’t matter. The only thing that mattered was the existence of an ‘agreement’. In addition to their assertion that I had an ‘understanding’ with Chan of Chicken of the Sea, the Government argued that I was a “hands on” CEO, and therefore must have been aware of the actions of Cameron and Worsham. The jury ultimately agreed with the Government that I must have known.

I did consider myself a “hands on” CEO and my management style included constant evaluation of performance data. Bumble Bee was a reasonably large organization with revenues of about $1 billion and I managed twelve individuals. I was not a micro-manager and I provided significant authority to my direct reports – especially ones like Cameron and Worsham who had both worked with me for more than a decade at that point in time. To manage the business I reviewed daily sales reports, weekly market shares and monthly financial performance. I met regularly with my executive team to discuss our business. And during the time period that the Government asserted there was a price fixing conspiracy, I saw rampant cost inflation, constant attacks on our business by StarKist and Chicken of the Sea, irrational pricing, and, for much of that time, falling profits. There was no indication of price fixing that I or anyone else could see.

The saga is now over and the Government has won – for now. While the Government argued fervently that I should spend ten years in prison for my “heinous” crime, the Court has sentenced me to 40 months in prison, 40 months away from my wife and son, for a crime I did not commit and a crime for which there was no victim. It is an unjust verdict based largely on testimony from ‘cooperating’ witnesses. It is an unjust verdict that I will appeal.

Was this prosecution an effective use of five years of Government effort? Was this purported crime so egregious and damaging to American consumers that it required the full force of the Department of Justice? Did it justify the massive expenditure of taxpayer funds?

And what about the impact on the U.S. tuna industry? Did the Department of Justice action justify driving Bumble Bee into bankruptcy? Was the $100 million fine levied against StarKist reasonable? Are the plethora of civil lawsuits, lawsuits that continue to this day, warranted? I estimate that the legal fees related to this action have exceeded $100 million and the only beneficiaries from this action by the Department of Justice have been the lawyers hired by those who have been accused.

My final question is does this outcome represent ‘justice’? Maybe in the mind of some it does but for me, the guilty verdict has shattered a 30 year career in the seafood industry, a career that I am proud of and where I feel I made a difference. For the company that I led for 20 years, it resulted in bankruptcy and the loss of investment for more than 50 managers who believed in Bumble Bee. And other than the lawyers, who has this prosecution by the U.S. Department of Justice benefited? There was no harm to any customer and there was never any financial effect of this purported price fixing conspiracy.

The legal power entrusted to the Department of Justice is capable of crushing almost any defense and is the primary reason that more than 90% of price fixing cases are settled out of court with guilty pleas – even when there may not have been any wrongdoing. I chose to fight, and I will continue to fight, because I am innocent.

Postscript — New Actions by the Department of Justice

The Department of Justice is now targeting the U.S. beef and poultry industries. Four of the largest beef processors in the U.S., Tyson Foods, JBS SA, Cargill and National Beef / Marfrig, who are said to control more than 80% of the domestic beef processing industry, have recently been subpoenaed. In the poultry industry, Perdue Farms, Tyson Foods, Pilgrim’s Pride, Sanderson Farms, Peco Foods, Wayne Farms, Koch Foods, Mountaire Farms and House of Raeford Farms have been in the news for price fixing and two CEO’s have recently been indicted. If the low bar of the Per Se rule is allowed to be applied to all of these companies, we may ultimately see our entire protein supply shift to foreign suppliers.